C.S. Lewis’ evangelistic influence has extended far beyond his own times. I know this firsthand: his words were instrumental in my own journey to faith.

Growing up in a Jewish home, I heard very little about Jesus. Religion meant reciting prayers, participating in rituals, and celebrating holidays. To me, the Almighty seemed distant and alien.

So, in my first year of college—aided by existentialist writers, Woody Allen movies, Kurt Vonnegut novels, and parties with large quantities of beer—I decided life was just absurd; it would never really make sense.

But even though I believed life was meaningless, I desperately hoped I would find something to prove that theory wrong. I loved music: perhaps that could provide the link to the transcendent, a connection to something beyond the material world. But every piece of music disappointed, every concert ended, and every noisy subway ride back to my dorm room contrasted rudely with the splendors of Dvorak, Rachmaninoff, and Mozart.

Little did I know, however, that I was already on a journey to saving faith.

Back in high school, one of my drinking buddies had invited me to his church’s youth group because, he said, “the girls are cute.” He was right, and I became a regular, albeit non-Christian, attender of that youth group’s many activities.

Along the way, I heard the gospel—a message I promptly dismissed as “something Christians should believe” but irrelevant to Jewish people because “Jews don’t believe in Jesus.”

But people at that youth group displayed a kind of relationship with God that I found attractive. They prayed about anything and everything, and urged me to read the New Testament, as well as a book by some English guy named C.S. Lewis. I read neither. But I remembered the title of the book: Mere Christianity.

Oddly, several years later, as I got ready for my sophomore year of college, I shoved the New Testament into one of my packing boxes. It remained in my closet as I resumed my absurd-reading, beer-drinking, concert-attending rituals.

All that came to a screeching halt when a friend died in a tragic accident.

Sitting at his funeral, I realized that Woody, Kurt, and Heineken could not provide the answers I longed for. “If there is a god, how can I know him?” I wondered. I went back to my dorm room and started reading that New Testament. I also checked out Mere Christianity from the library.

"C.S. Lewis’ evangelistic influence has extended far beyond his own times. I know this firsthand: his words were instrumental in my own journey to faith."

I read where nobody could see me. As I read Matthew’s quotations from the Old Testament and Jesus’ claims to be God, C.S. Lewis’s arguments stoked my searching. He eliminated one of my firmest convictions—that Jesus was just a good teacher.

I’ll never forget reading, “A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic—on a level with the man who says he is a poached egg—or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God: or else a madman or something worse.”

That convinced me that Jesus was the Messiah. But mere intellectual assent has never saved anyone. It was the other strand of Lewis’s presentation that pushed me over the line of surrender.

When I got to his chapter on hope, I saw why every concert left me feeling empty. After offering “two wrong ways” of dealing with life’s disappointments, Lewis wrote, “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

It was at the intersection of the intellect (Jesus was who he said he was) and imagination (I was made for another world) that the gospel became irresistible to me.

Sitting at my dormitory desk, I acknowledged that Jesus was not just the Messiah but my Messiah, the one I longed for in music and needed for atonement for my sins. Unlike Lewis, who said he came to believe in God “kicking, struggling, resentful ... perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England,” I rejoiced with singing.

It felt like a tremendous relief to receive music as a gift and not demand it be a god—and to have no need to perform rituals because I could rest in the finished work of the cross. I was overjoyed.

It’s the intertwining of the two forces of mind and imagination that, I believe, made C.S. Lewis such a powerful evangelist, not only for me but for countless others.

An expert on medieval literature may not seem like the kind of person God would use for widespread evangelistic fruit. But Lewis saw himself as a “translator—one turning Christian doctrine ... into language that unscholarly people would attend to and could understand.”

People listened to Lewis not because of his impressive qualifications but because he spoke in ways that made sense to them. We read his fiction today because it takes us to a land beyond a wardrobe. He appeals to our whole selves.

Lewis firmly believed that most of his books are evangelistic. That’s why it’s not only Mere Christianity but also his many other writings that we can learn from as we seek inspiration for evangelism. As part of my work, I once conducted extensive interviews of students about their conversions. Unsurprisingly, Lewis’s writings were mentioned frequently: not only Mere Christianity but The Chronicles of Narnia and his other fiction, as well as apologetic works like Miracles and essays like The Weight of Glory.

All these helped nudge people out of skepticism into faith. In one instance, it was a movie version of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader that ushered a theater major across the line of belief!

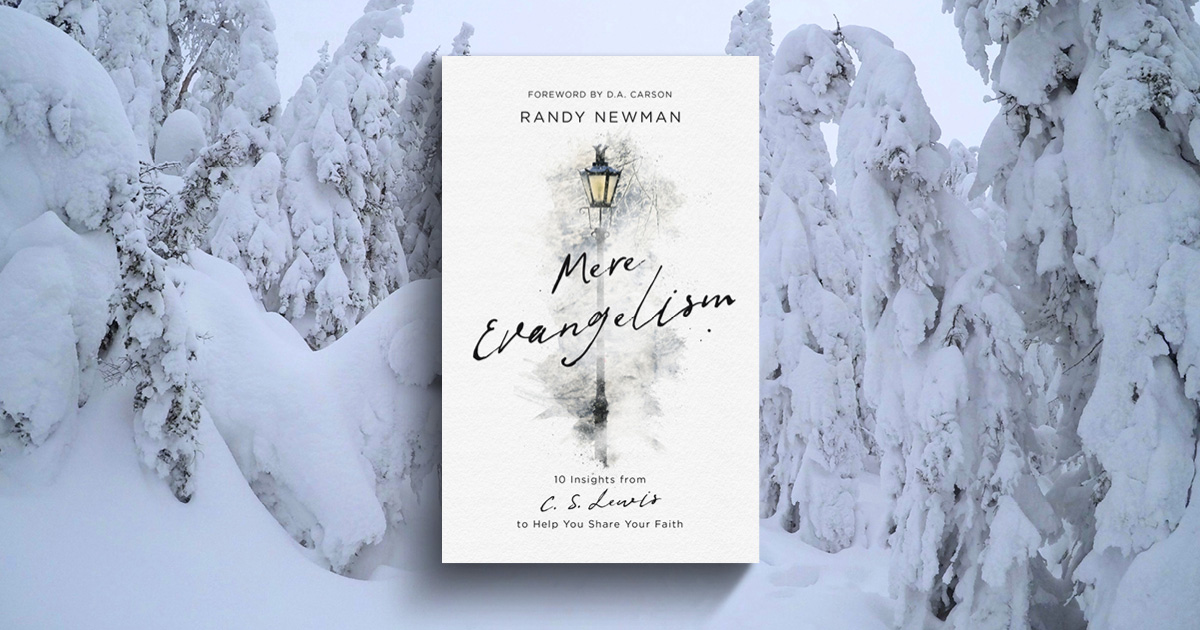

It’s with stories like these in mind that I wrote Mere Evangelism. By unpacking how this one far-from-ordinary evangelist did outreach, I believe we can equip ourselves in new ways for the extraordinary task of evangelism.

This article is adapted from the introduction of Mere Evangelism, by Randy Newman, which offers 10 insights from C.S. Lewis to help you share your faith. Through this book, you will be equipped to talk about your faith and engage with unbelievers wisely, whatever their attitude towards the Christian faith.